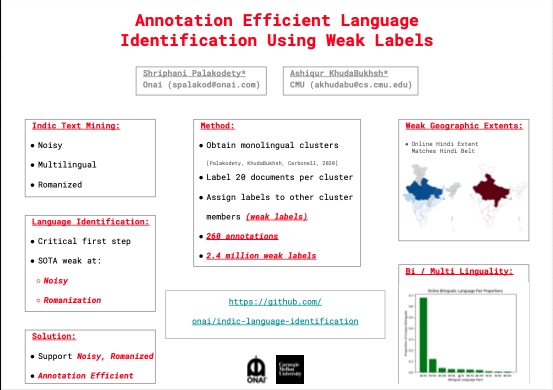

We discuss language identification of noisy, romanized text - an un-addressed but critical problem in Indic text mining, and release a language-identification utility. We then measure geographic extents of language use in India. Summary of a WNUT 2020 paper.

What aspects of Indic (possibly Arabic, Malay, etc.) text mining make it a more challenging undertaking than Western text mining. Our experience suggests:

- Noisy text

- Romanization

- Multilinguality

Noisy text refers to all forms of spelling and grammar disfluencies. English is a (distant) second language to most Indians and simple word-frequency based methods can fail.

Romanization is a widespread phenomenon in informal settings like social media and advertising. Hindi and other vernaculars are mostly written in the Latin alphabet. Our experience suggests this is the majority of the content authored in Indian social media.

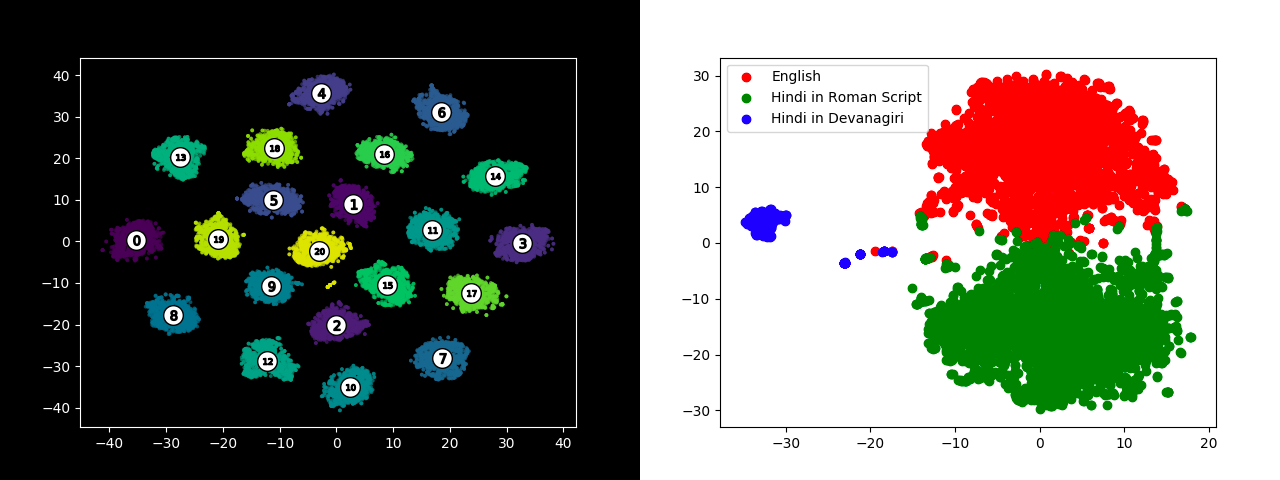

Multilinguality is a consequence of a high level of linguistic diversity in the Indian subcontinent. Any substantial corpus acquired contains a significant English, Romanized Hindi, Devanagari Hindi and several vernaculars (Romanized or native).

Language Identification is thus a critical first step in any Indic text-mining task. NLP pipelines and annotators are usually monolingual.

Existing resources for building good language identification systems focus on clean, well-formed text authored in the native script. Highly noisy, Romanized text is un-addressed by all existing tools.

We present a solution precisely for this problem - a lang-id system that works well on noisy social-media text, and handles Romanized Indian text content.

Our solution is extremely annotation-efficient - a mere 260 annotations are sufficient to construct a large data set of 2.4 million labeled documents.

Our solution uses a beautiful result on polyglot training from earlier this year.

Training a single skipgram model on a large multilingual corpus yields clean, well-separated monolingual clusters.

Our pipeline acquires these monolingual components, a skilled annotator labels a few (10 or so) documents from each cluster and we just expand these labels to the rest of the cluster members (we call these weak labels).

The end-result is a large labeled data set representative of social media content (the type that data-mining professionals are most interested in).

The resulting fasttext model is available in the links below.

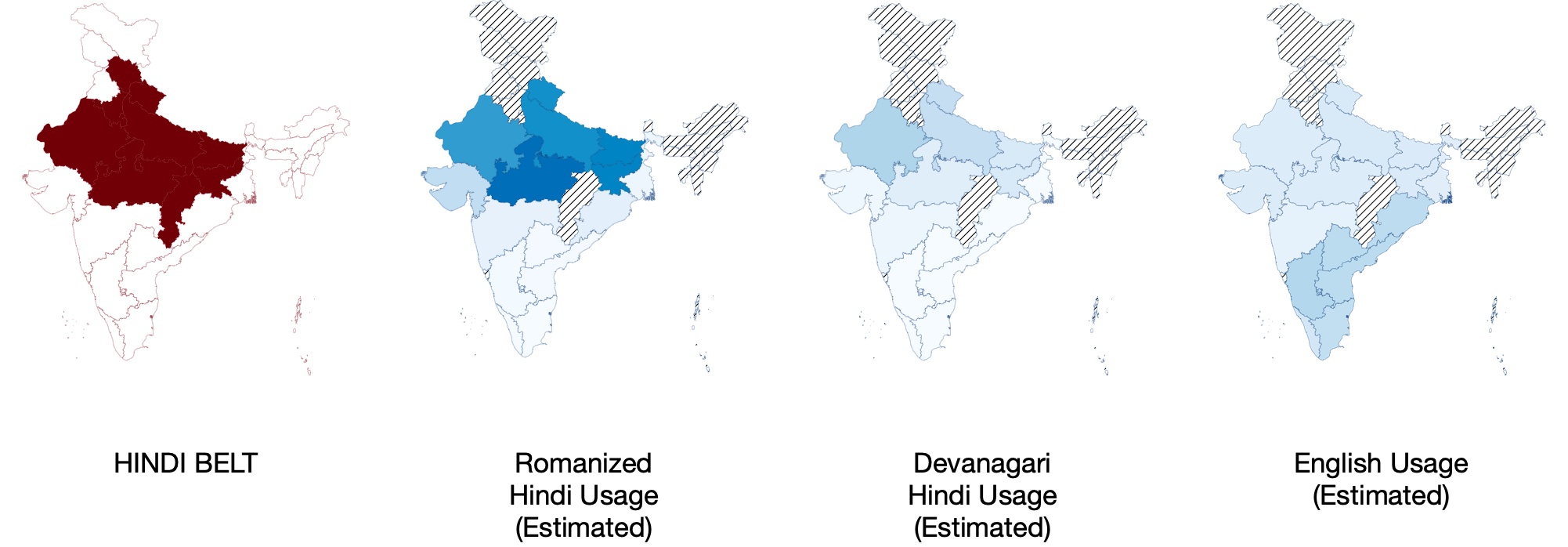

Geographic Extents

With our new language-identification system, and weak geo-labels from our corpus, we can estimate the geographic extent of languages. We observe that the estimate aligns with field-surveys like the Linguistic Survey of India. Hindi seems to be confined to an area popularly known as the Hindi belt, Romanization is the dominant form of expression in most of India. Online English usage as a percentage of the conversation is higher in Southern India. Bilinguals from areas adjacent to the Hindi belt use Hindi and their native language. As we enter Southern India, Hindi is nearly non-existent on social media.

Bi / Multi Linguality

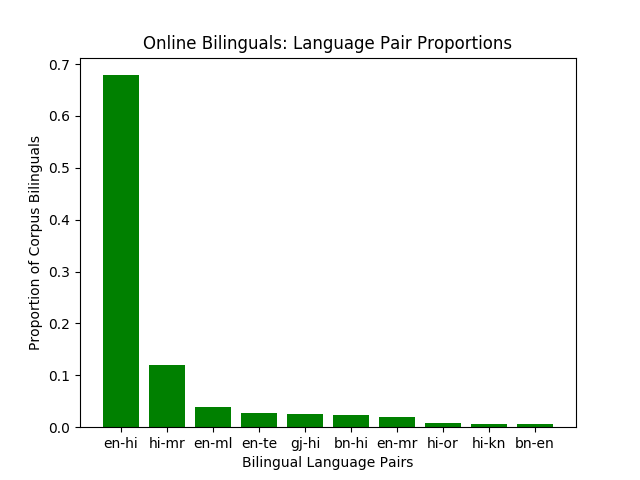

We next estimate what fraction of users post in multiple languages and what pairings (combinations) are most prevalent. The bulk of language-pairs we observe in bi-lingual users contain English, and bilinguals using 2 South Indian languages are extremely rare.

Links

In collaboration with Ashiqur KhudaBukhsh